The history of the Tour de France is filled with monumental stages and dramatic moments that have shaped the race into the iconic event it is today. Among these significant milestones is the first mountain stage in the Alps, which took place on July 10, 1911. This marked the first time the race ventured into the towering peaks of the Alps, a formidable challenge that would test the mettle of the cyclists and set a new precedent for what would become one of the most demanding and prestigious sporting events in the world.

Introducing Alps to Tour de France

The introduction of the Alps came just a year after the Pyrenees were included in the Tour de France in 1910. Prior to this, the Tour had primarily focused on flat or rolling terrain, but as the race evolved, so did the ambition of its organizers. Including the high mountains was seen as the next big challenge, and the Pyrenees provided the first taste of how grueling these stages could be.

The success of the Pyrenees in 1910, particularly the inclusion of the Col du Tourmalet, a mountain that would become legendary in the race's history, paved the way for the Alps. While the story of the organizers' first encounter with the Tourmalet was filled with drama, trepidation, and skepticism (Henri Desgrange, the race's founder, was initially hesitant to include such daunting climbs) the addition of the Alps was less contentious. By 1911, there was an understanding that mountain stages would push the limits of human endurance and elevate the prestige of the Tour.

Thus, the 1911 Tour de France introduced several iconic Alpine climbs, including the Col du Galibier, Col du Télégraphe, Col des Aravis, and Col de Lautaret. These "giants of the Alps" were not just hills or steep ascents; they were towering obstacles that loomed large over the race, both physically and metaphorically. Their inclusion signaled the Tour's transition from a long-distance endurance race to a battle against some of nature's most unforgiving terrain.

The story of the first Alpine mountain stage

The 5th stage of the 1911 Tour de France, which ran from Chamonix to Grenoble, was a grueling 366 kilometers long. It took Émile Georget 13 hours and 35 minutes to complete, a testament to both the distance and the difficulty of the course. This stage was the first time that riders would face the formidable heights of the Galibier, Télégraphe, Aravis, and Lautaret, all of which would become legendary in the history of the Tour de France.

The Galibier, in particular, stood out. At an altitude of 2,645 meters, it was the highest point ever reached in the Tour at that time, and it quickly earned the nickname "the giant of the Alps." Climbing the Galibier was a daunting challenge, with steep gradients, unpredictable weather, and rough roads that made it almost impossible to ascend without dismounting. Yet, three riders managed to do just that. Émile Georget, Paul Duboc, and Gustave Garrigou were the only cyclists in the peloton who did not dismount their bikes during the climb.

Georget's victory on the stage was hard-fought. He finished 15 minutes ahead of Paul Duboc and 26 minutes ahead of Gustave Garrigou, who was leading the general classification at the time. However, it’s important to note that during this period of the Tour de France (from 1905 to 1912), the general classification was based on points rather than the time gaps between riders. This meant that a rider’s overall standing was determined by their finishing position in each stage, rather than the cumulative time they had taken to complete the race.

The legacy of Col du Galibier

After the succesful introduction, the peloton stayed in the Alps for the next two stages. Stage 6, which took place on July 12, 1911, saw the riders tackling more climbs, including the Col de Laffrey, Col de Bayard, and Col d'Allos. These climbs were similarly challenging, though perhaps not as iconic as the Galibier. Two days later, in Stage 7, the riders faced yet more mountainous terrain, with the Col de Castillon and Col de Braus featuring prominently. Both stages were over 300 kilometers long, adding to the punishing nature of the race.

The success of the 1911 race, particularly the inclusion of the Alpine stages, ensured that the mountains would become a permanent fixture of the Tour de France. The Galibier, in particular, became one of the most iconic climbs in the race's history. The following year, in 1912, the Tour returned to the Galibier, cementing its status as one of the great challenges of the race.

Since its introduction in 1911, the Galibier has been featured in the Tour de France over 60 times, making it one of the most climbed ascents in the race’s history. Each time it appears on the route, it brings with it a sense of awe and anticipation. The climb has been the site of many dramatic moments over the years, from heroic solo breakaways to heartbreaking collapses. Its towering presence and the sheer difficulty of its ascent make it a true test of a cyclist's endurance, strength, and determination.

MORE STORIES FROM THE EARLY YEARS OF TOUR DE FRANCE

Eugène Christophe, the unluckiest cyclist ever

In the world of professional cycling, few names are as synonymous with misfortune as Eugène Christophe. His legacy… Read More »Eugène Christophe, the unluckiest cyclist ever

Tour de France’s first visit in the Alps (1911)

The history of the Tour de France is filled with monumental stages and dramatic moments that have shaped… Read More »Tour de France’s first visit in the Alps (1911)

MORE TOUR DE FRANCE IN THE ALPS

Eugène Christophe, the unluckiest cyclist ever

In the world of professional cycling, few names are as synonymous with misfortune as Eugène Christophe. His legacy… Read More »Eugène Christophe, the unluckiest cyclist ever

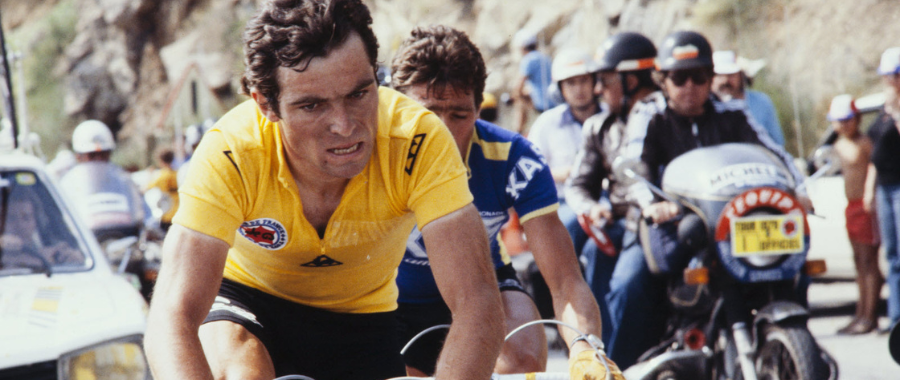

When the Badger backed down: Bernard Hinault’s controversial withdrawal (Tour de France1980)

In the pantheon of cycling legends, few names carry the ferocious weight of Bernard Hinault. Known as “Le… Read More »When the Badger backed down: Bernard Hinault’s controversial withdrawal (Tour de France1980)

Would you like to take a look at the mountain stages (including the ones jn the Alps) of Tour de France 2025?

Click here to take a quick look at all the stages of Tour de France 2025